Disclaimer: This edition of Neural Notes was heavily inspired by the works of Luke Burgis and the article he wrote for PSYCHE.

Should you pursue job X or job Y? Should you start that business or should you wait? What would people think? How do we make the choices that we make? Why do we pick one thing over the other? Life is made up of choices and it is crucial to decide which ones are worth selecting and which ones aren’t.

“Desire (as opposed to need) is an intellectual appetite for things that we perceive to be good, but that we have no physical, instinctual basis for wanting – and that’s true whether those things are actually good or not,” writes Luke Burgis.

We have intellectual appetites and physical ones, too. Solving a problem, getting a text from a loved one, and understanding a difficult concept are all the joys that fill intellectual appetites. This joy can sometimes spill over into the physical realm of our being.

Desire, by definition, is something that we lack and strive for. The physical appetite ushers a person into an ever-eternal strive of wanting more without fully satiating his hunger.

Desires Are A Social Process - They Are Mimetic

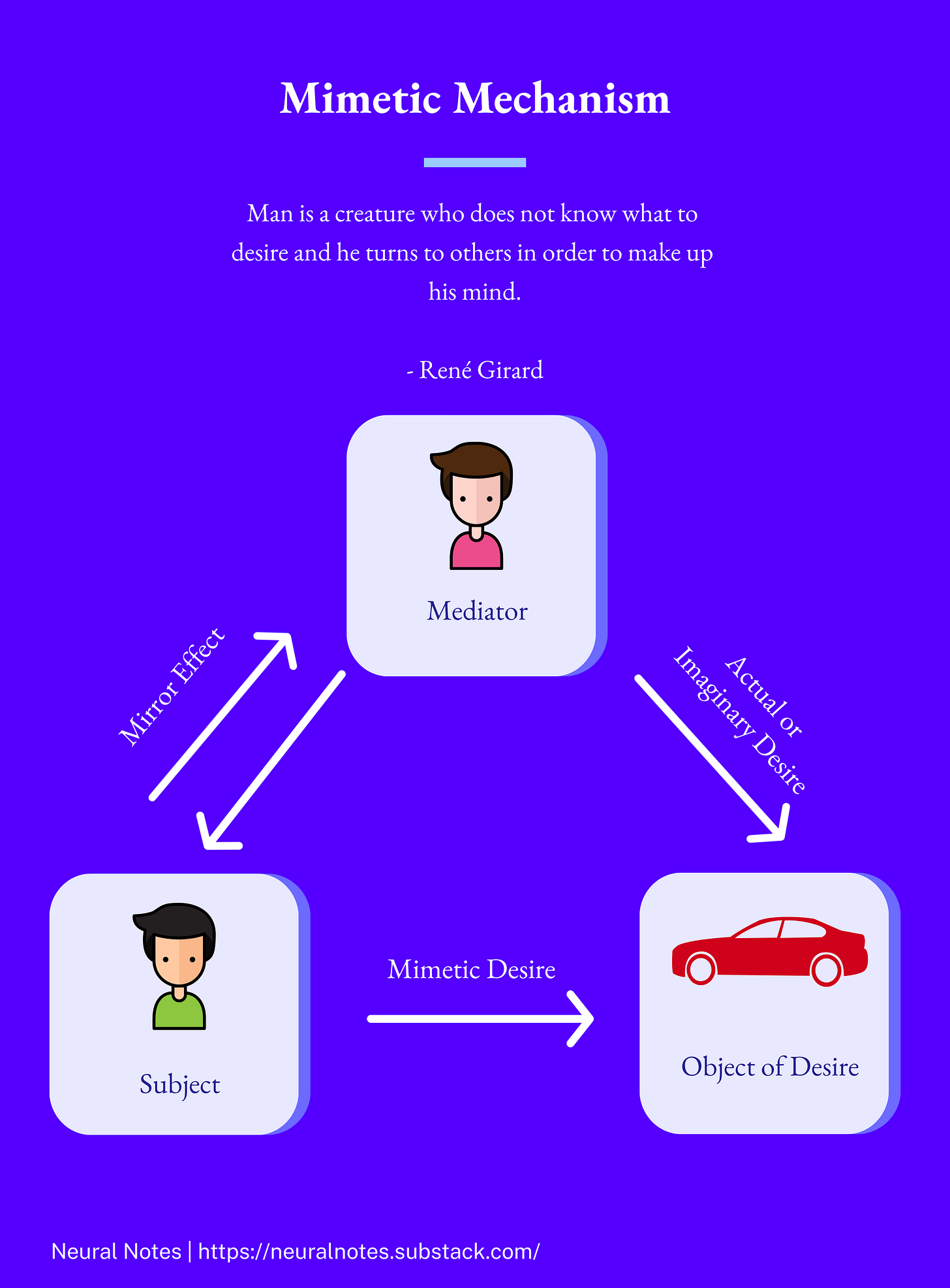

René Girard (December 25, 1923 - November 4, 2015) was a world-renowned French historian, literary critic, and philosopher of social science. Girard claimed that human desire functions imitatively, or mimetically, rather than arising as the spontaneous byproduct of human individuality. In simple terms, our desires are not our own. They are a product of us imitating our immediate environment.

‘Man is the creature who does not know what to desire,’ wrote Girard, ‘and he turns to others in order to make up his mind.’ He called this mimetic, or imitative, desire.

Mimetic desires are the desires that we mimic from the culture and people we are surrounded by. If there is an object, lifestyle, or career that we deem as good, it is because someone has modeled it that way for us to find it appealing.

We all pattern our choices on somebody else's example. It might be a celebrity we've never met or it could be the best friend we've known all our lives. We desire what others desire. Advertisements also model desires to us, obviously, but notice how they usually work: the companies serving the ads typically show us not the thing itself, but other people wanting the thing. We humans, as social creatures, know others so we can know ourselves. However, if we are not careful enough, we can become obsessed with others. And advertisers play right into our mimetic nature. Interestingly enough, it doesn't even have to be a real person for us to model after.

Types of Models

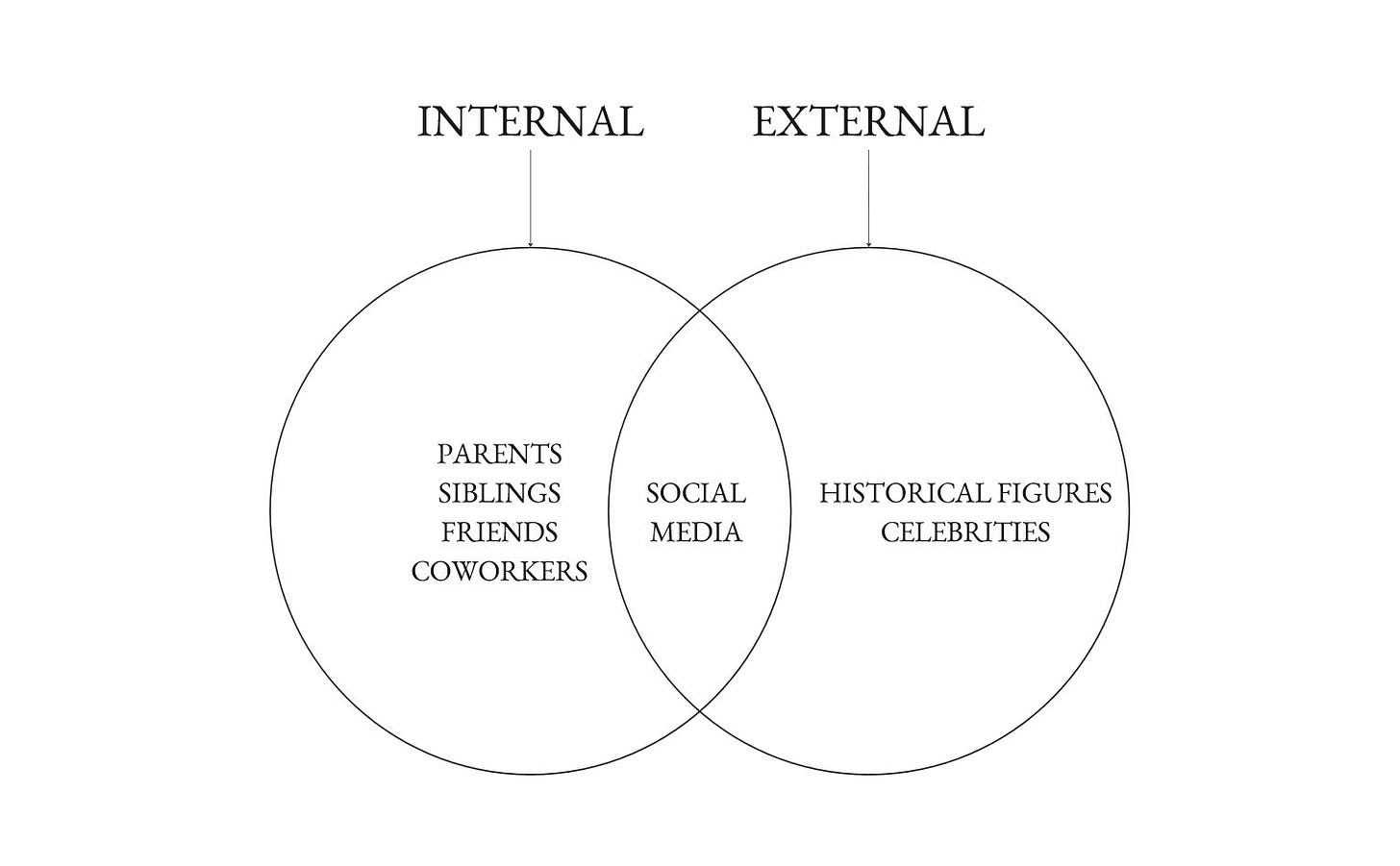

There are two classes of models we follow in our lives:

Internal Models

External Models

Internal models are the people in our immediate surroundings that we are in contact with: Parents, Siblings, Friends, or Coworkers. Our desires are intertwined with these people in one way or another. They can also affect our desires and vice-versa.

External models are the people we are unlikely to come in contact with: Historical figures, Singers, Actors, and much of our legacy media. For instance, we cannot come in contact with James Cameron after watching Avatar. The caveat when it comes to external models is that they are one-way streams. These external models can affect us through their works, but there is no way for us to affect them.

Adding Fuel To The Fire - Social Media

If it were the 1700s, there weren’t numerous external models for us to hunt after apart from the occasional newspaper gossip. Au contraire, the modern-day society that is powered by the internet exposes us to hundreds, if not thousands, of external models. It isn’t a shock then why we are all on a massive hedonic treadmill. Social media is a mimetic machine. What we typically call ‘social media’ is really social mediation – the mediation of desires. All day, every day, desires are being modeled to us through people we barely know. Mimetic desire is the hidden engine of these platforms.

The more someone is closer to being like us, the more we can relate to them. So, social media puts these external models just enough in our perimeter for us to reach for them, but not enough for us to turn them into internal models. Who are most people more jealous of? Elon Musk, the richest man in the world? Or the colleague who went to the same high school as them but is making an extra $10,000 a year? The latter, of course. The difference between the internal and external models makes this adequately clear.

“Because desire is mimetic, people are naturally drawn to want what others want. ‘Two desires converging on the same object are bound to clash,’ writes Girard. This means that mimetic desire often leads people into unnecessary competition and rivalry with one another in an infernal game of status anxiety. Mimetic desire is why a class of students can enter a university with very different ideas of what they want to do when they graduate (ideas formed from all the diverse influences and places they came from) yet converge on a much smaller set of opportunities – which they mimetically reinforce in one another – by the time they graduate,” explains Luke Burgis.

Working out who our internal and external models of desire are (and which ones are in the grey area) will help us gain greater agency over our desires.

Think It Through

Desires originate in us from social influences in a gradual way that makes them inconspicuous until it is too late. We need to become more aware of who, not what, has shaped our desires by asking these questions:

When I think about the lifestyle that I would most like to have, who do I feel most embodies it?

Aside from my parents, who were the most important influences on me in my childhood?

Is there anyone I would not like to see succeed? (Negative models of desire)

Ideally, drawing a Venn and writing down our internal and external models of desire including the grey ones will enable us in achieving more control over our desires.

Stuck In A Spider Web of Desires?

It is conceivable that most of the choices we make aren’t formed as the sum of individuals around us, but because we might be stuck in a system that forces our choices of desire. For instance, in order to keep the ratings of his restaurant from crashing, a chef may cease to experiment with new ingredients and stall his ingenuity for passivity. Likewise, the kid who is desperate for the approval of his parents on his academic performance spends all his time studying and never tries his hand at his favorite sport. We have to figure out what version of this web we are stuck in. Uncovering our web of desires will eventuate in us taking a step back and not accepting dominant desires that drive our behaviors at face value.

We will never know what an authentic desire is unless we figure out where it comes from. All desires have a history. Some of them can be recent and some of them can be deep-rooted in us since our childhood.

Is There Any Originality Then?

Imagine the desires on a spectrum. On the left side are the less mimetic desires and on the right end are the extreme mimetic ones.

The less mimetic desires on the spectrum could include a person’s religious beliefs that don’t necessarily change based on encounters with other people or the environment. They are deeply ingrained in the person’s psyche.

The more mimetic desires on the right end of the spectrum could be following the status quo in order to feel accepted as a part of the herd or to avoid the fear of missing out. A quintessential example would be buying a particular stock or product by a celebrity only because others are buying them.

We are the sum of desires of everything and everyone we are exposed to that has had a deep impression on our will. This, however, doesn't mean that there is no originality within us. There can be ten different people desiring the same thing, but all of them come to convergence in their own nuanced way. It is possible for a desire to start as fully mimetic and over time turn into less mimetic.

Take the example of Ferruccio Lamborghini. He started manufacturing sports cars after being humiliated by Enzo Ferrari, a purely mimetic move. Decades later, Lamborghini had forged a name for himself in the world of automobiles by carving his own path, becoming less mimetic.

Freedom: An Anti-mimetic Life

An anti-mimetic life is one where a person is free from blindly following their desires without knowing their origin. It is freedom from the herd mentality. A person with robust underlying values—either religious or philosophical—will be less susceptible to being blown away by the winds of temporary mimetic desires. Anti-mimetic life is about becoming a conscious consumer and sitting in the driver’s seat. It is deciding who to surround ourselves with, what sort of content to consume, and what models to look up to. The ancient wisdom ‘you are the average of five people you surround yourself with,’ might just be much deeper than we thought.

P.S: I still want a Lamborghini😉